NES4JAMS is a comprehensive Integrated Development Environment (IDE) for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), built entirely as a plugin for the JAMS platform.

This project was developed as my Bachelor’s Thesis in Video Game Design & Development. The primary engineering goal was to validate the flexibility of the JAMS architecture by injecting a completely foreign instruction set (8-bit MOS 6502) into a platform originally designed for 32-bit MIPS RISC architectures.

The Motivation

Developing homebrew games for the NES typically involves a fragmented workflow: writing code in Notepad++, assembling via command line (CLI), and testing in third-party emulators. NES4JAMS unifies this pipeline. It provides a modern experience with intelligent code completion, visual asset editors, and cycle-accurate debugging in a single window.

Written 100% in Kotlin, it serves as the ultimate “Stress Test” for the plugin API, proving that JAMS can evolve beyond its initial scope without modifying a single line of its core code.

The NES Toolchain

Unlike simple emulators that just play ROMs, NES4JAMS provides the entire pipeline to create them from scratch.

:: MOS 6502 Assembler

A custom assembler supporting the full 6502 instruction set and undocumented opcodes. It handles iNES headers and complex Bank Switching directives required for Mappers.

:: Cycle-Accurate PPU

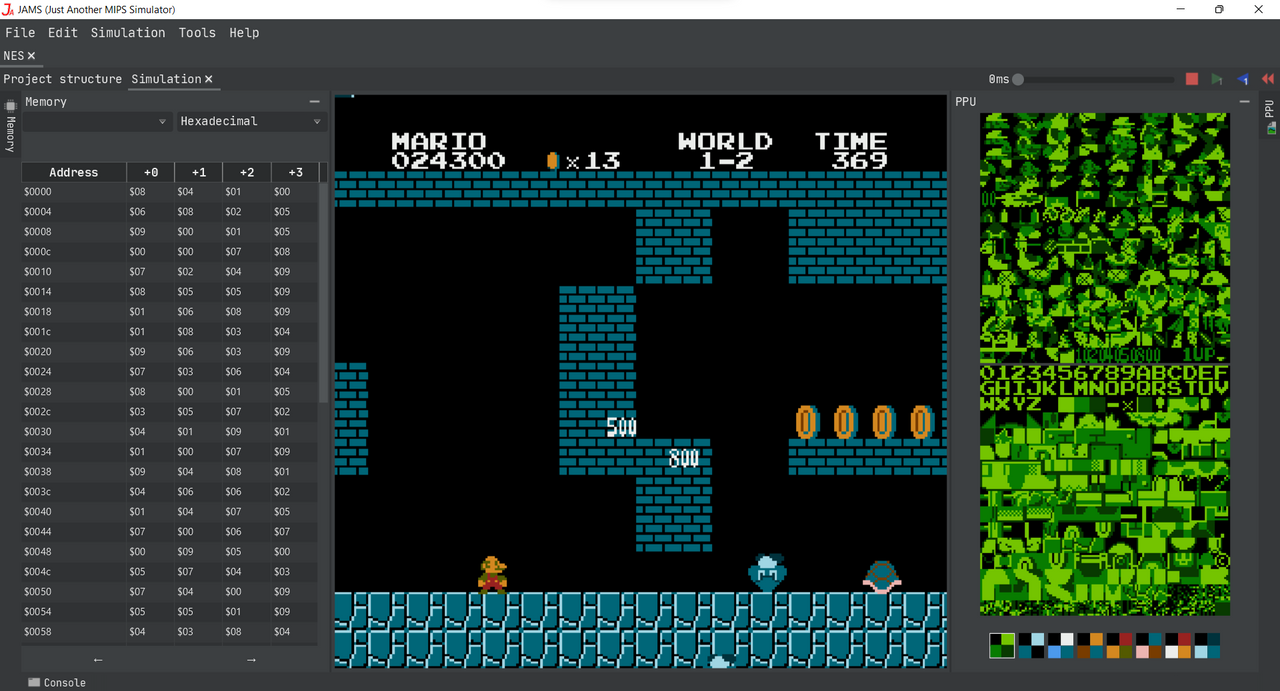

A scanline-based emulation of the Picture Processing Unit (2C02). It renders graphics pixel-by-pixel, respecting strict timing constraints to support raster effects like split-screen scrolling.

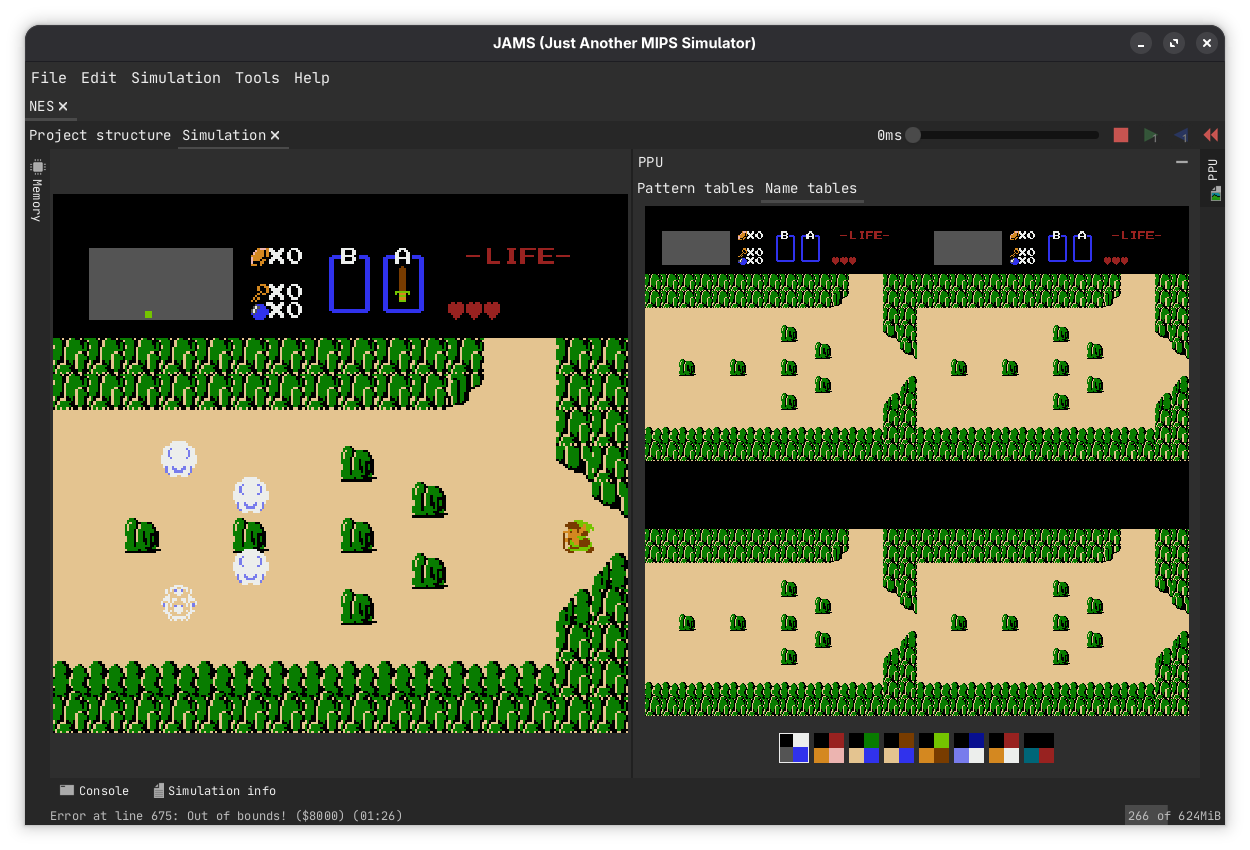

:: Visual Debuggers

Includes specialized tools to inspect the NES internals: Pattern Table viewer, Palette editor, and a real-time Nametable scroller to visualize off-screen rendering.

:: Asset Pipeline

Integrates a Tile Editor for .chr files and supports importing PCX images, automatically quantizing

them to the NES 4-color palette limitations.

Hardware Emulation Architecture

While the MIPS simulator was built from a clean ISA specification, the NES is a beast of undocumented hardware quirks. Games from the 80s often relied on undefined behaviors and precise timing glitches to achieve visual effects, turning emulation into a task of archaeological reverse-engineering.

1. The PPU: Racing the Beam

The Picture Processing Unit (2C02) doesn’t render frames but pixels. The emulation loop must be strictly coupled to the CPU clock to support “mid-scanline” effects.

- Pixel-Perfect Timing: The PPU runs at exactly 3x the speed of the CPU (NTSC). I implemented a Catch-up Scheduler that pauses the CPU whenever it accesses a PPU register, runs the PPU for the exact missing cycles, and then resumes. This allows games to change scroll positions during the drawing of a single frame (e.g., Super Mario Bros 3 status bar).

- Hardware Limitations: Unlike modern engines, the NES has hard limits. I emulated the 8-sprites-per-scanline limit, causing the authentic “flicker” seen in retro games when too many enemies align horizontally.

2. The Mapper Jungle

The NES CPU can only address 64KB of memory, but games grew much larger. Nintendo solved this with Mappers: custom chips inside the cartridge that physically re-wired memory banks on the fly.

- Polymorphic Memory Controller: I architected a flexible

Mapperinterface. The emulator intercepts memory reads/writes and routes them through the active Mapper implementation. - Bank Switching: The implementation of complex banking logic (like MMC1 or MMC3) allows games like Metroid or Zelda to swap entire 16KB code pages or 4KB graphics pages instantly.

3. The “Quirks” Factor

Authenticity lies in the bugs.

- Mirrored Memory: The NES address space is full of “mirrors”. Writing to

$2000is the same as writing to$2008. The emulator’s memory bus implements this shadowing logic transparently. - Open Bus Behavior: Emulating what happens when you read from unmapped memory (returning the last value on the data bus) is critical for some games to boot (like Super Mario Bros. 3).

- Undocumented Interrupts: The NES has a few undocumented hardware interrupts that can be triggered by the CPU. I implemented a simple IRQ System that allows games to trigger custom actions at specific points in time. This is vital for games like Silver Surfer or, again, Super Mario Bros. 3.

The Integrated Workflow

Developing for 8-bit hardware typically involves a “Frankenstein” toolchain (external tile editors, command-line assemblers, hex editors). NES4JAMS consolidates this into a single, cohesive pipeline.

1. The 6502 Assembler Backend

I extended the generic JAMS assembler architecture to support the MOS 6502 instruction set. Unlike the uniform 32-bit MIPS instructions, the 6502 is variable-length and heavily reliant on addressing modes.

- Bank Management: The assembler includes specific directives (

.bank,.org) to manage the fragmented memory layout of NES cartridges. Developers can explicitly place code in specific 16KB PRG banks to support Mapper switching. - Advanced Macros: Supports the full JAMS macro system, allowing high-level constructs to be compiled down to raw assembly, improving readability without sacrificing cycle control.

;; Example: Defining the Interrupt Vector Table in NES4JAMS

.bank 1

.org $FFFA ; Jump to the end of the cartridge memory

.dw nmi_handler ; Non-Maskable Interrupt (V-Blank)

.dw reset_handler ; Boot/Reset vector

.dw irq_handler ; External Interrupt / BRK2. The Asset Pipeline (CHR & PCX)

Graphics on the NES are stored as “Pattern Tables” (2-bit tiles). Editing hex values directly is impossible.

- Visual Tile Editor: I built a dedicated editor for .chr binary files, allowing users to draw sprites and tiles directly within the IDE.

- PCX Import: To bridge the gap with modern art tools, the IDE imports PCX images. It automatically quantizes and slices standard images into valid 8×8 NES hardware tiles, managing the strict 4-color palette limitation automatically.

3. The iNES Linker

The assembling stage can be defined as a structural packaging process.

The system generates an iNES Header based on the project configuration

(Mapper ID, Mirroring Mode, TV Region) and stitches the compiled PRG

and CHR banks into a valid .nes ROM file ready for deployment.

Technical Challenges

The Catch-Up Problem (CPU-PPU Sync)

The NES PPU renders pixels in parallel with the CPU. Games rely on cycle-perfect timing to execute “mid-scanline” tricks (like changing scroll splits). A standard frame-based update loop breaks these effects.

I implemented a Catch-Up Scheduler. Whenever the CPU accesses a hardware register, the emulator pauses the CPU and “fast-forwards” the PPU for the exact number of cycles elapsed. This guarantees synchronization at the sub-instruction level [cite: 3567-3570].

Audio Signal Processing (1.79 MHz)

The NES APU generates audio samples at the CPU clock rate (~1.79 MHz). Playing this raw stream on modern hardware (44.1 kHz) causes severe aliasing and buffer underruns.

I implemented a Weighted Averaging Downsampler. It accumulates the high-frequency samples generated during a frame and compresses them into a time-weighted average before sending the buffer to the host audio driver, ensuring clean sound without artifacts.

The Event System Bottleneck

JAMS uses a reflection-based Event Bus for modularity. While great for the UI, firing a generic event for every CPU cycle or Memory Write (millions/sec) destroyed performance.

I bypassed the generic JAMS Event Bus for the “Hot Loop”. The emulation core uses Direct Memory Access interfaces and specialized listeners for hardware IO, reserving the high-level Event Bus only for low-frequency UI updates (like pausing or loading a ROM).

Dynamic Cartridge Rewiring (Mappers)

The NES CPU can only address 32KB of ROM, but games are much larger. Cartridges contain custom chips (“Mappers”) that physically rewire memory banks on the fly.

I architected a polymorphic Mapper Interface.

The emulator intercepts every memory fetch. If the address falls into cartridge space,

the active Mapper translates the virtual address to the physical offset in the loaded

.nes file, enabling instant bank switching for games like Metroid.